The Consolation is the product of the dramatic circumstances that ended its author’s life. While the medieval audience, for the most part, responded to its more obvious features, its hidden complexities and subtleties are what can open its appeal to readers now. The Consolation is a far more subtle work than it at first seems to be. But, if read carefully, in its historical and literary context, it should do. Unlike Plato’s dialogues, for instance, or René Descartes’s Meditations, it no longer seems to carry a broad philosophical appeal. Yet now the work is the preserve of scholarly medievalists. Although Aristotle’s texts shaped the university curriculum, and Augustine’s thought was ubiquitous, in the period from 800 until about 1600 no other philosophical text could compete with the Consolation in its appeal – not just to the intellectual elite but to a much wider audience too.

It was read not only by those who could understand its 6th-century Latin original but also those who studied it in any of a multiplicity of translations, into Old and Middle English, Old French, Old High German, Italian, Spanish and many other languages, including Greek and Hebrew.

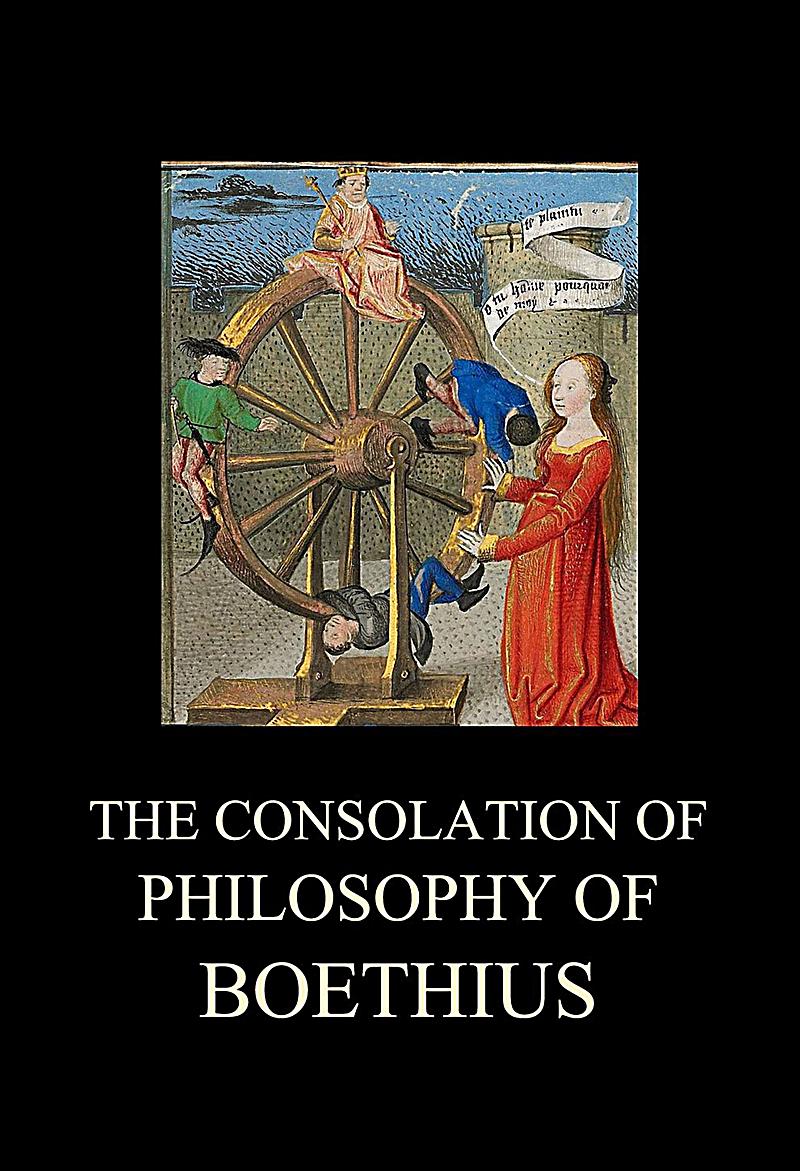

And in an introduction intended for the general reader, Seth Lerer places Boethius’s life and achievement in context.For nearly a millennium, The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius was a bestseller throughout Europe. In an artful combination of verse and prose, Slavitt captures the energy and passion of the original. Composed while its author was imprisoned, cut off from family and friends, it remains one of Western literature’s most eloquent meditations on the transitory nature of earthly belongings, and the superiority of things of the mind. 480–524), an Imperial official under Theodoric, Ostrogoth ruler of Rome, found himself, in a time of political paranoia, denounced, arrested, and then executed two years later without a trial. Those less familiar with Consolation may remember it was written under a death sentence. The result is a major contribution to the art of translation. His prose translations are lively and colloquial, conveying the argumentative, occasionally bantering tone of the original, while his verse translations restore the beauty and power of Boethius’s poetry. Slavitt preserves the distinction between the alternating verse and prose sections in the Latin original, allowing us to appreciate the Menippian parallels between the discourses of literary and logical inquiry. Slavitt presents a graceful, accessible, and modern version for both longtime admirers of one of the great masterpieces of philosophical literature and those encountering it for the first time. In this highly praised new translation of Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy, David R.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)